Now that I’ve gone all-in on a graphics programming kick, I’ve been watching a ton of videos on graphics fundamentals. The other night, I stumbled across a YouTube video titled “One Formula That Demystifies 3D Graphics” by Tsoding, and it absolutely blew my mind.

The video revolves around one deceptively simple formula that projects a point in 3D space onto a 2D screen:

{x, y, z} → { x / z, y / z }At a high level, this assumes your “screen” is centered at the origin (0, 0). Any point in 3D space is pulled closer to that origin the farther away it is along the z-axis. In other words, objects appear smaller as they move away from the camera. Exactly what you’d expect from perspective.

I’m still working on how to explain this purely with words, as I was failing at getting my freinds to understand this, but it really clicks once you see it visually. Thankfully, Tsoding does an incredible job walking through the idea step by step, building a simple demo from scratch using nothing but an HTML canvas, a bit of JavaScript, and some very approachable math.

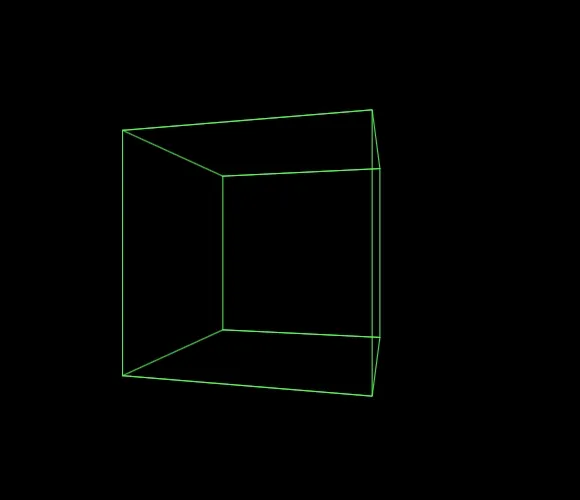

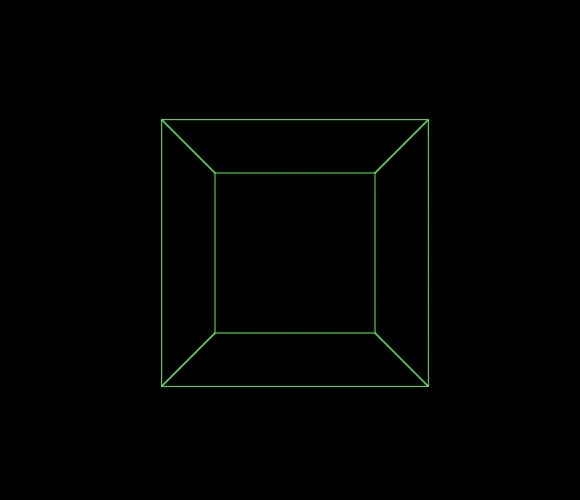

By the end of the video, you’re looking at a convincingly rotating 3D cube rendered entirely in software. No engines, no libraries — just math. Seeing that come together was insanely exciting.

Once I had the cube rendering, my brain immediately jumped to the next question: how do you move the camera? If I wanted to place multiple objects in a scene, I needed a way to move around the space and view things from different angles to really sell the 3D effect.

At first, I assumed camera movement was some kind of black-magic math that I wasn’t ready for yet. But after staring at this rotating cube for a while, I had a bit of a lightbulb moment. I remembered learning — mostly from game dev videos — that very large 3D worlds can run into floating-point precision issues far from the world origin. One common trick to work around this is to keep the player near the origin and move everything else instead.

That’s when it clicked: to “move the camera,” I didn’t actually need to move the camera at all. I could just move the cube in the opposite direction.

I added some basic keybinds, introduced camera position variables, and applied their inverse to the cube’s transform. And just like that — it worked. The cube responded exactly how a camera-relative object should. Adding camera rotation on top of that was the final piece; suddenly it genuinely felt like I was moving through 3D space.

At this point, my mind started racing with possibilities. Building what is essentially a tiny, baby 3D graphics pipeline from scratch has made modern graphics APIs feel far less mysterious. It’s amazing how much of it boils down to a few core ideas and some linear algebra.

Next, I want to experiment with things like simple keyframe animation or building a small environment that you can “walk” around in. This feels like my first real self-directed graphics project, and I’m excited to keep pushing it further — expect a more dedicated and organized project post soon.